BOOKS | CULTURE

My First Antiquarian And The Manly Art of Poetry

March 1, 2016

A long time ago, in what seems to be a parallel universe that's my sorely-missed real home to which I cannot return, my parents and I, on many a Saturday afternoon, went to vigil Mass at St. Ignatius Church on Calvert Street in downtown Baltimore. In Baltimore Saturdays I explain why we Bethesdans spent so many weekend days in that city 35 miles distant.

St. Ignatius was built in the 1850s in conjunction with Loyola College, forerunner of the university, which occupied the remainder of the block facing Calvert Street. The old college buildings are now Center Stage. Like St. Aloysius, its contemporary sister church in Washington, DC, St. Ignatius is modeled on The Gesu in Rome. Also like St. Aloysius, the Calvert Street church boasts artwork by Constantino Brumidi, a painting of the Jesuit founder in ecstasy that hangs on the south wall. Inside the front doors, one can still find old gas-light fixtures, long capped off, but mutely standing their ground against lighting progress.

St. Ignatius in 2013. Brumidi's Ignatius in Ecstasy is on the wall at left. Photo by Neal J. Conway

Around 1990 St. Ignatius' mid-19th-Century glory was restored, however in the 1970s, its statues and fluted columns, moldings and gildings were all covered with many coats of white paint. Saturday vigil Mass was attended by a very senior crowd. The usher, a spry, diminutive man who raced around with the collection basket, was born in 1890. The other regulars were of the same vintage. The only one whose name I learned was Mrs. Utermohle. She and my Dad had some mutual acquaintance and she came to Mass from the Mt. Vernon neighborhood wearing a black hat and veil over her face. The other octagenarians, I suspect, drove from the suburbs to worship where they had all their lives. It's strange to think that these people that I saw at least once a month, virtually contemporaries of H.L. Mencken, who no doubt remembered the Great Fire of 1904 and who perhaps played with Baltimore's own Voltamp electric trains, are all long dead. The painted-over St. Ignatius seemed to be a secret place known only to them, my parents and me.

St. Ignatius' upper church being too large to light and heat for such a small crowd, Saturday vigil Masses during the latter years of our Baltimore excursions were held in the dingy basement chapel, a space since completely lost to remodeling.

At one Mass, the celebrant directed everyone's attention to a dark corner where there was a table laden with old books for sale at twenty-five cents each. My parents and I were the only ones interested. The volumes had no library stickers and were mostly from the 19th-Century with the oldest ones having 1850s copyright dates. They had probably been acquired for the St Ignatius rectory from the time it was built.

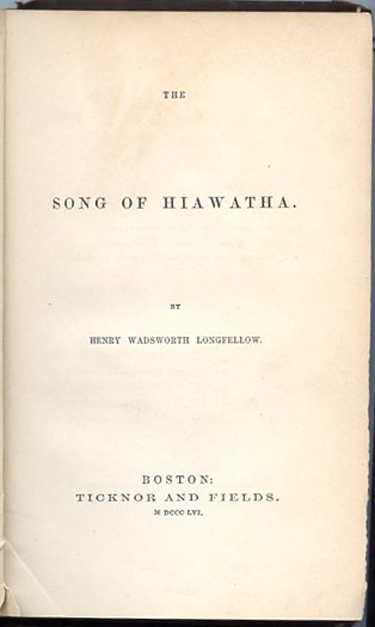

Leaving an honor payment, we came away with several, chosen mainly because they were the oldest and looked cool. One volume had hosted one of several insects known as bookworms which had bored through the rag paper and hollowed itself a chamber in the middle. Another was an enormous volume of saints' lives with engravings. Another contained lectures of Nicholas Wiseman, England's first above-ground Catholic cardinal in 300 years. The lot included a childrens' book of moral tales that, I gathered, had been translated from German with the Teutonic-vested children in the illustrations (and cultural situations) retained. The moral of one tale was: Be kind to Jews. Given my current interest in pre-Civil-War Catholicism and its media, I should have kept all these. However the only book of that haul that has stayed with me through the years and the disposition of the old homestead and its extensive collection of collections is an 1856 copy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The Song of Hiawatha.

Fourteen-year-old me had heard of Longfellow. In fact, the summer we spent in Cambridge, Mass., we had rented a few blocks from the poet's house on Brattle St. What kid of my generation could have watched Saturday morning cartoons without catching Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny in Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt which concludes with Bugs reciting, "Westward, westward Hiawatha / Sailed into the fiery sunset...."? That cartoon was in part funny to the 1940 audiences who first saw it because many a kid back then had to memorize parts of the poem in school. My mother could still summon from her twelve years at St. Leo's in Ashley, Pennsylvania:

By the shores of Gitche Gumee,

By the shining Big-Sea-Water,

Stood the wigwam of Nokomis,

Daughter of the Moon, Nokomis.

Dark behind it rose the forest,

Rose the black and gloomy pine-trees,

Rose the firs with cones upon them;

Bright before it beat the water,

Beat the clear and sunny water,

Beat the shining Big-Sea-Water.

I figured that this 25-cent find was worth researching. From some source in those dark ages before Google, I learned that Longfellow had written the poem in 1855. Did we have the first printing? I remember Dad and I looking it up in a book about old books. The first printing from late 1855 was valued at 200-some dollars. However that's not what we had. Ticknor & Fields first printing of 5,250 copies has a few errors in it, e.g., "Wahonomin" instead of "Wahonowin." We had a specimen of a later printing of 25,000 from 1856.

After that, The Song of Hiawatha, unread by me, was put behind the glass doors of the secretary and remembered only when it had to be moved.

As was not the case with my parents and generations preceding them, poetry, particularly epic poetry, figured almost not at all in my education. With the exception described in the next paragraph, my schools did nothing to dispel the impression that poetry was something that rhymed and that if it didn't rhyme, it was defective or boring. Modern poets have destroyed poetry for the layman just as modern philosophers have destroyed philosophy for same. Also, a visiting alien anthropologist would be given the impression that the only verse worth reading was written by Maya Angelou. Educational faddishness and its snooty attitude toward memorization also pared back that vital learning exercise to practically nothing.

The Song of Hiawatha ... is so countercultural to the early 21st-cenrury vision of boyhood and manhood. That modern vision is to wit: Men are the evil empire of stupid dolts and rapists. Men must be emasculated and the process must start in boyhood.

St. Ignatius

At Georgetown Prep I was exposed to a bit of Homer's Odyssey and The Divine Comedy. We read something about King Arthur, but it was not of Tennyson's authorship and our vision of Arthur as a cartoon character never evolved into a vision of Arthur as a great Christian legend. Virgil's Aeneid, a staple of education for 1500 years, was covered only in the chapters of a second-year-Latin book. It was in second-year Latin, taught by the wonderful Rev. James A.P. Byrne, S.J., that I learned that poetry can also be written in meter. I struggled with metric verse. It was one of those things that I have a hard time understanding. However I still remember Fr. Byrne exemplifying dactylic hexameter with "This is the forest primeval, the murmuring pines and the hemlocks."

That was the only line of Longfellow I got in school. At the time I got no pleasure out of hearing or reciting it.

The Manly Art of Poetry

My discovery of the poetry that my generation had missed out on began a few years ago. I have long admired the steel engravings of Gustav Doré, the 19th-century French illustrator who brought his gift for making the unreal seem real to editions of Danté's Divine Comedy, Tennyson's Idylls of The King, Poe's The Raven to mention a few. I picked up works to look at Doré's picture's and started reading the verse alongside them.