PLACES TO GO

Jarboe Grove's

Manor Woods

April 1, 2021

Families that enjoy success, wealth and power generation after generation, I suspect, develop a familial culture of being able to recognize, almost by instinct, where money can be made. This is certainly true of the Carroll Family which still holds, after over 300 years, a good deal of land in central Maryland.

In the 1700s Charles Carroll of Annapolis bestowed thousands of choice acres, called Carrollton Manor, on his son Charles, also giving the latter the lordly title of Charles Carroll of Carrollton. The younger Carroll was later a signer of The Declaration of Independence and the only Catholic to sign it.

Carroll houses were often neither large nor ostentatious. Private property, "Tuscarora" still stands. Visitors in the early 1800s included St. Elizabeth Ann Seton's daughter, Catherine.

Located in southern Frederick County, Maryland, between present-day Routes 85 and 15, the Carroll estate extended from Ballenger Creek, just south of Frederick to the Potomac River, including the towns of Point of Rocks and Buckeystown.

The Carrolls leased most of their land to others for generations. One plot was leased to a church for the rent of "one rose a year."

Around 1820 the family provided acreage for the construction of a Catholic church now known as St. Joseph's on Carrollton Manor. Located on Manor Woods Road and built of abundant, local limestone, the old church, which took final form just after the Civil War, retains some walls of the original 1820s structure. In 2014, the parish built a fine, new church with an interior of rich wood that recalls seldom-tributed American Catholic church design of the early 1800s.

Limestone: the earth of Carrollton Manor was imbued with its fertile residuum. The limestone itself, when burned in kilns, was also a source of mortar. The mortar was used in the construction of the U.S. Capitol Building and in the stone aqueducts on the nearby Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Canal. A couple of these water bridges, at Mouth-of-Monocacy and near Brunswick, stand fully intact for bikers, hikers and joggers. Another at Seneca was heavily damaged by Tropical Storm Agnes in 1972. The last of the old lime kilns in Lime Kiln, just north of Buckeystown, was demolished out of safety concerns in 2016.

Once known as Licksville, a name recalled only by a short stretch of road, Tuscarora, Maryland boasts a post office but no other public buildings or business district. This structure dates from the 1860s and was perhaps originally a general store.

The Carrolls' land was also rich in timber, locust wood, good for shipbuilding and in demand as far away as England.

The family appreciated the boons of the Potomac and Monocacy Rivers flowing by their estate. The C&O Canal was a conduit of goods and commodities to Georgetown for almost a century. Even before the C&O made the Potomac Valley navigable in the 1830s, there was, on the Virginia side, a bypass of the Great Falls of The Potomac which made possible water transport to Georgetown and Alexandria.

Another clan prominent in Maryland, particularly Frederick County, the Johnsons, used the waterways to transport the output of their iron furnaces which dotted the countryside. Catoctin Furnace near Thurmont is a remnant of the Johnsons' industry. A couple of their manor houses endure nearby.

Driving on bucolic Routes 28 and 85 today, perhaps passing another car every couple minutes, one has a hard time conceiving that, 200 years ago, 85 and portions of 28 and other roads through Tuscarora were part of a major thoroughfare from The South to The West. Nolands Ferry on the Potomac, now a nowhere with nothing, was a heavily-trafficked crossing to Virginia.

Up these roads in 1755 came General Edward Braddock, with young George Washington on his staff, marching to Braddock's fatal encounter with the French and Indians at Fort Duquesne. Up the same paths connected to Old Georgetown Road came hundreds of rough men in buckskin, hoping to join Braddock's expedition. But Braddock turned up his nose at them. His defeat by the French and Indians has been attributed to insufficient forces.

Certainly the Carrolls made use of the roads and even built a road some 30 miles from Carrollton to their interests around Ellicott's Mills, an early industrial town that the Carrolls hired Andrew Ellicott to develop. But transport with horsepower on unpaved roads was slow, inefficient and very expensive. When it came to tobacco, rather than hauling it with oxen, it was less onerous to just roll huge barrels of the leaf down Rolling Road.

When Charles Carroll of Carrollton was an old man, a new kind of road appeared in his country. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was the first U.S. rail carrier of both freight and passengers. Carroll, a director, welcomed it on his property with a donation of right-of-way.

The first track built out of Baltimore consisted of iron rails laid on granite ties. This proved to be excessivly costly. Stone masons had to cut grooves in each tie. By the time the track-layers reached the Carrollton-Manor area in the early 1830s, the B&O had switched to redesigned track using iron straps on wooden rails.

As trains became larger and heavier, the original right-of-way, which went around every tree and rock, was straightened and re-routed. The granite ties were taken up and recycled. B&O buffs know how to spot these ties re-used in early stone bridges and other works. There are even some heavily-rusted strap rails on the original right-of-way to be found if one knows where to look.

The man we will meet shortly wrote that when rails evolved into the T-form on wooden cross-ties still used today, some discarded early strap rails were used in the building of houses in Lime Kiln, Maryland. Intact strap rail from the 1830s would be quite a historical find. One wonders if any of these structures endure among the old mid-19th-century houses of this little hamlet that borders Buckeystown.

The railroad followed the Patapsco River, then the Monocacy for a bit. After passing over flat country and between hills, it came to Point of Rocks where the barrier of mountains was breached aeons ago by the Potomac River, allowing a passage into the river's valley.

At Point of Rocks in 1832, the B&O Railroad met the C&O Canal. There these rivals in transportation halted their building to fight each other. For the rocky "point" of Catoctin Mountain nearly touched the river and allowed little room for the passage of both conveyances.

After two years of court-fighting, proposals, counter-proposals and legislative action in Annapolis, the B&O agreed to finance the canal to its terminus in Cumberland and buy stock in the waterway. This, in the end, left the railroad the outright owner of the canal which it operated and maintained for the next 90 years.

Enter William Jarboe Grove

Along the B&O Railroad, in the midst of his father's lime kilns and mills, around 1854, was born William Jarboe Grove. He was descended from Dutch Graefs and French Catholic Jarboes who appeared in Maryland in the 1600s. William's father, Manasses, was also the B&O's agent in Lime Kiln. His mother was a member of St. Joseph's parish.

When he was in his seventies, Jarboe Grove wrote a thick volume, History of Carrollton Manor(1). Despite all the deficiencies of a book self-published by an amateur author with a few years of one-room-school education (no editing, lack of clarity, repetition of material, parroting of common sentiments of his day, digressions into personal opinions, even resizing of type to fit material into what is already an excessive amount of pages.) History of Carrollton Manor is as fascinating as it is rare.

In Jarboe Grove's reminiscence of Frederick County Maryland life in the 19th century are mentions of jousting, the official state sport of Maryland. While the term "jousting" invokes images of heavily armed knights charging at each other with likely injurious or fatal consequences, the sport as practiced in Maryland since colonial times involves lancing suspended metal rings. Jousting tournaments are still held throughout central and northern Maryland in the summer months.

Old Hundred Road along the border of Montgomery and Frederick Counties near Sugarloaf Mountain is a curious name. It may be named after a pitching game that Jarboe Grove describes as consisting of a board with numbers on it, the number 100 being in the center. A player won if his pitched penny landed on 100.

Northern Maryland has long had a generous portion of strange phenomena, particularly around Emmitsburg. Jarboe Grove reports that in the summer of 1861, a "cloud of fire" could be seen traveling South over the heavens until it reached "the section of Harper's Ferry." It appeared on a Sunday night and a Thursday night of the same week. The light it shed was as bright as daylight. With the Civil War getting under way, with Harper's Ferry already being a magnet of conflict and with the common belief of the time that the world would soon end, many Frederick Countians were frightened. It's likely that what they saw in the heavens was Comet Thatcher which visits every 400 years or so.

B&O memories

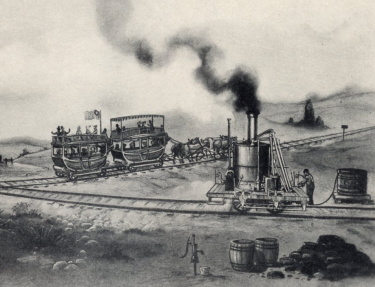

Jarboe Grove could remember "the horse car tree," where the B&O shaded horses in those early years when teams of quadrupeds pulled the trains. He also records having seen "grasshoppers," primitive B&O locomotives so called because the drive rods powered by their vertical boilers resembled a grasshopper's legs. It appears that both horses and "grasshoppers" were used as motive power on the B&O long after historians have hitherto believed.

When Jarboe Grove was about five, a train passed through Lime Kiln Station carrying a Maryland militia group known as the Junior Defenders. Like other antebellum paramilitary groups of the time, these had a connection with a Frederick firefighting company. (p. 200) Led by John Ritchie, later Maryland's Attorney General, they were on their way to Harpers Ferry to confront John Brown. Jarboe Grove recalled that in 1861, a conductor on a train announced at Lime Kiln station that South Carolina had fired on Fort Sumter. "Now Hell is to play," said a bystander (p. 209). Having the telegraph, the railroads often learned of happenings before anyone else.

Drawing of an unknown location on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad from the days (1830s-40s) when trains were pulled by horses and primitive steam engines called "grasshoppers."

One of the Buckeystown Buckeys was a B&O engineer. He drove an engine called "Buckey's Eel Trap." Somehow, in 1862, the loco spent some time on its side in the Potomac River from which it was fished and rebuilt by the Mount Clare Shops.

In June of 1877 there occurred a terrible wreck near Point of Rocks, likely on the B&O's newly-built Metropolitan Division. Extended a few years after the Civil War from Washington through Gaithersburg, Rockville and Silver Spring, it met the original main line from Baltimore at Point of Rocks. Like a couple other gruesome, high-casualty train wrecks of the 19th Century, the 1877 incident involved an excursion train (i.e., not on the regular schedule) and the extreme mayhem of wooden passenger cars that, on impact, were pushed inside each other like the segments of a telescope. Among the injured and killed were members of prominent Frederick County families: Schley, Bartgis, Buckey.

Civil War

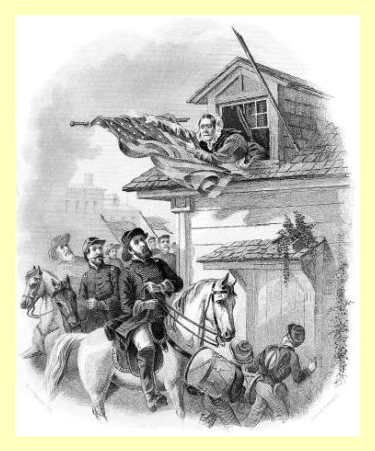

Well into the middle of the 20th century, schoolchildren had to memorize John Greenleaf Whittier's poem, Barbara Fri[e]tchie(2), about an old lady who confronted Antietem-bound Stonewall Jackson on his march through Frederick in 1862 when the general, according to the poem, ordered a soldier to fire at Widow Fritchie's U.S. flag staffed outside her dormer window.

While Frederick and its Chamber of Commerce got a lot of mileage out of The Fritchie Legend, Fritchie, 95 in 1862, was bedridden, a couple months from death. Stonewall Jackson did not pass her house on his march through Frederick.

Still, some young women in Frederick County got in the Confederates' faces with the U.S. flag. When Jackson actually encountered a couple, he bowed and doffed his hat in keeping with the legend of his good nature.

Despite some residents' fidelity to the Union, most of Maryland, especially Jarboe Grove's neighborhood (and indeed, many residents of Washington, DC), was sympathetic to the Confederacy. Federal troops swarming through the state to protect the nation's capital just after the attack on Sumter were regarded as invaders. The Feds indeed planned to arrest secessionist Maryland legislators; citizens were detained at Fort McHenry without being charged.

President Abraham Lincoln is the "despot" whose "heel is on thy shore" in the state's former official anthem, Maryland, My Maryland by James Ryder Randall.